An Object of No Place

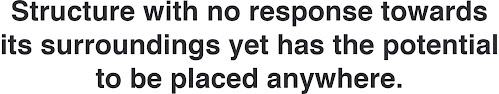

Around that time, the world was shocked with the appearance and disappearance of a number of enigmatic monoliths that had emerged in multiple states in the United States including one in Romania. It was a huge internet sensation for over a month as its form truly resembles that in the famous science fiction film by Stanley Kubrick, 2001: A Space Odyssey – thus, giving rise to speculation about an extraterrestrial-related source of origin.

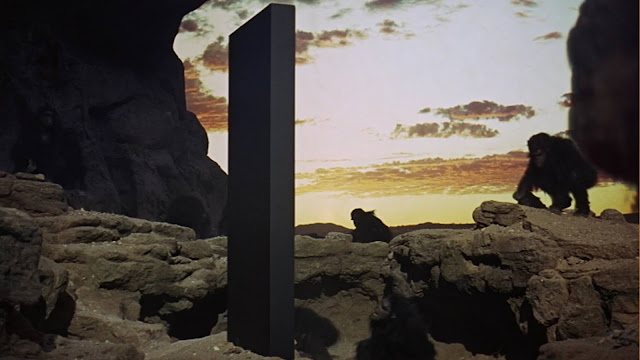

The juxtaposition of The

Exchange tower’s crown with monolith’s body structure is intended to connect

the elements of “alienation” between both structures in terms of its odd-placement

in context and the public’s response towards the subject matters.

The monoliths are rigid

objects placed in an organic context - yet why do they look like they belong

there? Like they have always been there? Is it because of this weird combination

of structural-context elements that made people go crazy on them? Now observe

the picture below..

Can we agree that The

Exchange Tower serves the same external quality? The newly developed and rigid

shape of the tower (1) does not serve a significant contribution towards KL

Skyline, (2) does not compliment the harmony of existing super-tall-structures

in Kuala Lumpur (KLCC, Menara KL), (3) looks very secluded, introverted and

alienated within its extended context – yet, its presence in KL skyline is not

exactly a sin. It’s as though we completely reject what reality NEEDS to

offer, and we, the urbanites, just simply embrace our physical environment

(even the stuff that “sucks”) with our modern conveniences and inclination for

the sense of denial.

In addition, we can

also see that The Exchange Tower’s appearance in the skyline of Kuala Lumpur bear

a resemblance to the work of Japanese painter Minoru Nomata - who’s famous for

visualising a progressive language of imaginary buildings, monoliths including

hybrid aerostate. Most of his works radiate a sense of deja vu that echoes the

styles of “ancient monuments of forgotten civilisations with a futuristic

feeling that sometimes underlined by enigmatic technological inventions” even

though they do not exist in reality.

But unlike the works of the Japanese painters, The Exchange Tower is real. In fact, the subject matter in the paintings signify a distinct symbol of status, power, absolute and control while we can simply say otherwise for the physical appearance of the tower.

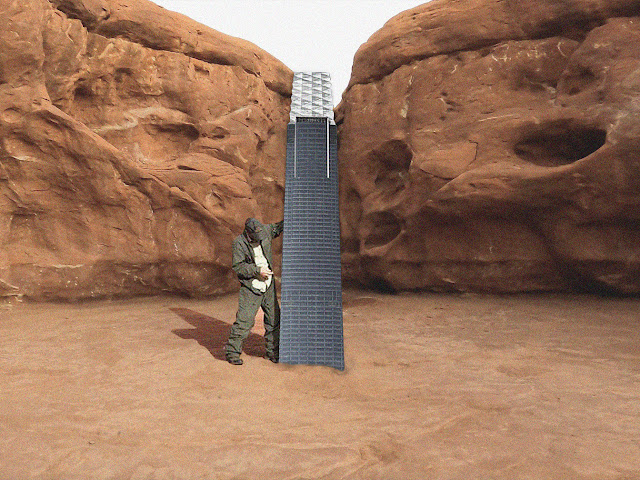

Besides, it is justifiable that The

Exchange Tower actually has the potential of being an “alien” structure. Alien

works well in terms of its architectural language, disruptive to surrounding

context, and its form and appearance operates as a non-contextual anomaly -

which is very much acceptable if we take a step back to look at the bigger

picture.

Now that we’ve established the distinct internal similitude between these subject matters (the monolith and The Exchange Tower), what if we try switching their respective surrounding contexts to see what happens?

It is directly proven that, just like the infamous monolith placements, it IS possible to place The

Exchange Tower in any metropolitan skyline as we can see that the apparent disconnect between context and this skyscraper's

design clearly highlight its individualistic/egoistic design that obviously

does not mirror its extended urban context,

which begs the question: does this non-contextual architecture promise greater

design potential or is it actually an inevitable issue?

We must keep in mind

that one of the subject matters is a mixed-use tower in a well-planned business

district and is “the embodiment of elegant sophistication and the nation's

ambitions” as its official website states, while the other is merely an entity

of a lifeless object.

Non-contextual architecture, in definition,

is a design approach which focuses on the needs of the architect and of their

client, involving design solutions that do not necessarily create desirable

places. The institutional form itself often becomes an object to be manipulated

at will [to] achieve the maximum gratification of the desires and needs of its

designers and owners. The "non" part basically means not having a

context - meaning that it does not have a built-in relationship with its

surroundings (including other skyscrapers) or any other structure in any urban

context.

When it comes to architecture without

context; it’s not necessarily just about attention-seeking and extraordinary

structures. The design intention can be used to create new trends and design

languages, not only in terms of aesthetics, but also as part of a sustainable

or radical movement.

This write up is beyond doubt an attempt to widen the spectrum of the term’s definition by exploring its potential within the context of our subject matter.

Within the context

that we’re on, we believe that the built “form of design” of The Exchange Tower

have the potential to be the genesis of a movement which proves that

reproduction of the same content of design is possible to be put elsewhere in

any metropolitan cities.

If we go a little bit deeper, perhaps,

this movement will help unravel strings of predicaments in terms of (1) design

authority where it can act as a "motif in a pattern" where future

potential projects now have a form to lean on which leads to endless scaled

templates (2) set up a language for the brand where

one can use the same design approach to create sense of familiarity for the

brand and (3) acts as a symbol (be it of power or capitalism) where it will

serve the “maximum gratification of the desires and needs of its designers and

owners”.

There’s still space for this topic to

be developed, for the reason that the built form is contradicting in itself; it

can be both good and bad altogether – resulting in an emotional paradox. One

thing for sure, the impact of good architecture will inspire a surge of growth,

progress, and revival. And its only good that we conclude this write up with an

excerpt from the book, Citizens of No Place by Jimenez Lai;